DISCOVERING

THE SILENT WAY

by John and Susana Pint

©2005 by John and Susana Pint

Excerpt from Part II:

Teaching Spanish to Beginners

A Fourteen-hour Intensive Course

By Susana Pint

SOLVING A NEW PROBLEM: WRITING

About six hours have gone by (with three breaks in between) and we are coming to the end of the day. After this kind of preparation, my students are indeed ready to solve a new problem: writing.

I take a look at the notebook where I have been jotting down some of the words we have used throughout the day.

The subject matter of the sentences I will give them will be restricted to what we have worked on. As a preamble, I give them a visual dictation using the charts, the Fidel and the words we have written on the blackboard. They respond orally. After this reading and speaking exercise, I mime writing and they take their notebooks and pens. The visual dictation I now give them is similar to the previous one, but now all of them are engaged in the new challenge of writing down what they have mastered orally.

The few examples below will give the readers an idea of the fields of study we touched upon (not just through the rods) during the first day of work:

Por favor, toma tres regletas blancas y

pon una aquí, dos allí, y la otra dásela a X.

Gracias.

De nada.

Ahora toma diez azules y dámelas.

¿Cómo se llama la persona que esta allí?

No sé.

¿Y tú, sabes?

No. Yo tampoco sé.

¿Dónde está la regleta negra

y dónde están las amarillas?

Todas estan aquí.

¿Chisuko esta aquí o está allá?

Chisuko está allí.

The following dialogue, which also formed part of the dictation, is actually an exchange I had with one of them earlier. It shows that I had taken advantage of a special situation where they could sense the meaning of what I was putting in front of them. It also shows that we had become so close to each other that we could share our sense of humor:

¿Tú entiendes?

No. No entiendo.

¿No entiendes nada?

No. No entiendo nada.

¿No entiendes absolutamente nada?

No. No entiendo absolutamente nada.

¡Pobrecito!

¿Qué es “pobrecito”?

.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.

They have the sentences written in their notebooks and I go to the blackboard and divide it into three parts. I write a number at the top of each section:

|

1-

|

2-

|

3-

|

(Figure S-46)

I take three marking pens and offer them to the group and mime writing while indicating the blackboard. Three volunteers stand up and I gesture to them to take their notebooks. As I give a marking pen to each of them, I show them which of the sentences in their notebooks each is supposed to write. When these three students have finished, I write three more numbers, corresponding to the next three sentences. We continue this way until all of the sentences have been written.

To make the corrections, I use one of my favorite techniques. I stand by the blackboard and pass the pointer through sentence #1. With a questioning look in my eyes, I ask them, “¿Sí?” which for them means is it/he/she correct? with only two choices for an answer, si or no. (While doing this exercise, I will watch for opportunities to give them alternatives, both for questions and answers.)

They look at the sentence attentively and I wait for the answer. The sentence on the blackboard reads:

Por favor, toma tres regleta blancas y

ponla una aqui dos alli y la otra da se

la a ella.

Kimiyo says “No” and I hand her the marking pen and the eraser so she can correct whatever she has found wrong. She adds an s to the word regleta, looks over the sentence and goes back to her seat. Without any special expression on my face I pass the pointer through the sentence again. “¿Si?” I ask them. After a moment of silence, Paco says, “No,” stands up and erases the last two letters in the word ponla. He carefully looks at the sentence again and goes back to his seat. I repeat “¿Si?” and wait. They say, “Si” —not too sure of themselves— and I “underline” da se la with the pointer, making the joining gesture with my fingers. I offer the marking pen and the eraser and another volunteer stands up, erases the three syllables and writes dasela.

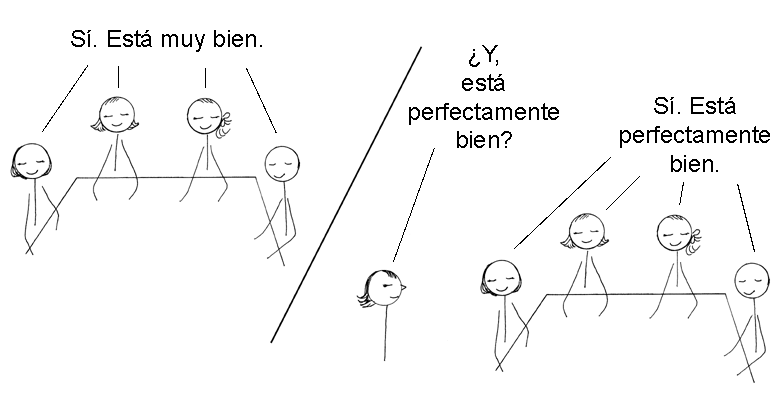

There is complete silence and their eyes are fixed on the sentence. I pass the pointer through the sentence once again and this time I don’t ask “¿Si?” but “¿Está bien?” (Is it all right?) They don’t seem to have noticed I have given other words to my question, for they continue looking at the sentence. “¿Está bien?” I ask again. They look at me and at least two voices say a very positive “Sí”. I move my head negatively, and with a facial expression that says, “Sorry, folks!” I gently tell them, “No... no está bien.”

Suddenly it dawns on them that we are using a new expression and that they have picked up its meaning instantaneously. They look at me with amazement, understanding, trust. I again tell them, “No está bien,” point at the accent on the Fidel and “underline” with the pointer the words dasela, aqui and alli. Very softly they say the words, looking for the place where the accents should be. At this point, Chisuko stands up very calmly and writes an accent on the i of the word aqui and looks at me. I tell her, “Sí, sí” and she continues by writing an accent on the i of allí. She hesitates when coming to the word dasela and I tap out the word on the table with my knuckles. She immediately writes an accent on the first a of the word and goes back to her seat.

They all continue to look at the sentence and I’m amazed to see how easily they give themselves to this job... as if they were willing to give it all the time in the world. I can’t keep myself from showing them my admiration through a smile. “¿Está bien?” I ask them once more and point at the sentence. They look at me with sparkling eyes and one of them says, “Está bien,” emphasizing the first syllable of the first word. I “tap out” the rhythm of the sentence on the table, using the pointer. “¡Está bien!” they say and play with their new discovery, repeating the words over and over.

I go to chart #1 and touch the word sí. Then I “transport” the accent from the Fidel to the i in si and gesture for them to say it and continue. I hear a general, “¡Sí! ¡está bien!” and I continue my questioning: “¿Y, está muy bien?”

(Figure S-47)

Actually there is still a comma missing, so I tell them, “Bueno. . . está casi perfectamente bien” —during the course we had used the word casi (almost). I “draw” the comma with the pointer, between the words aquí and dos and a volunteer goes up and writes it. The sentence now reads:

Por favor, toma tres regletas blancas

y pon una aquí, dos allí y la otra

dásela a ella.

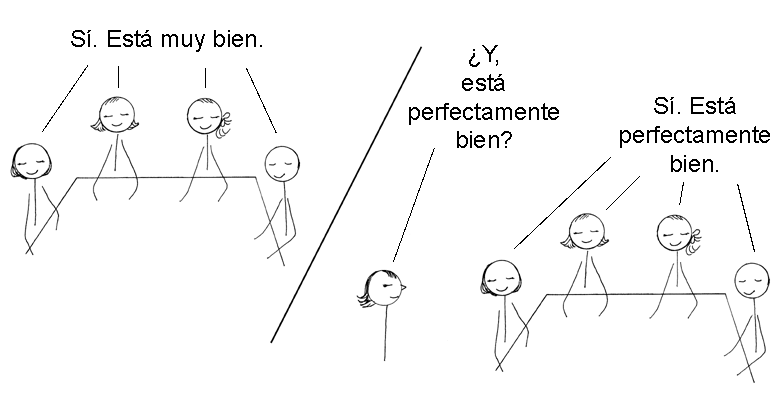

Continuing on with sentence #2, I don’t pass the pointer through it, but only touch the number. “¿Está bien?” I ask them in a very quick manner. The rather short sentence is indeed correct and I see a jubilant expression in everybody’s eyes:

(Figure S-48)

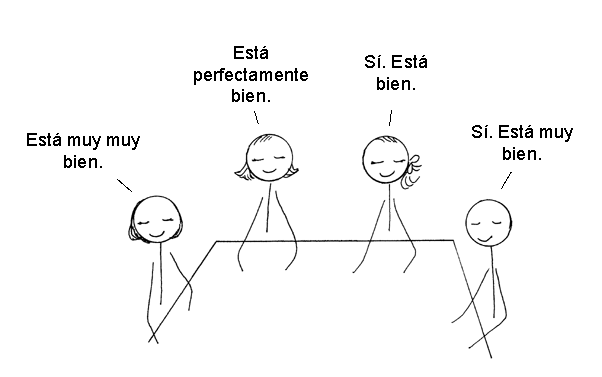

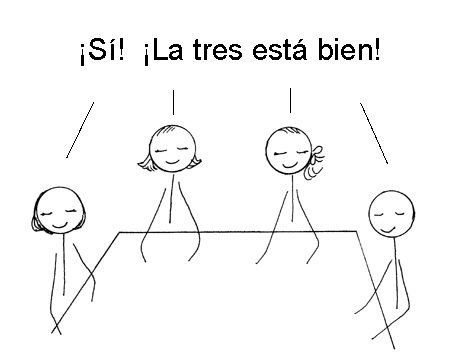

We go on to the third one also very short but this time I don’t do anything except ask: “¿Y, la tres, está bien?” They look at the sentence and then at me, as if trying to make sense of my new question. “¿Y la tres, está bien?” I ask them once more and point at the number. They look at it. Again, I see sparkling eyes: “Si... la... tres... está bien.” I gesture that they should speak faster.

(Figure S-49)

With a very quick movement I turn to Kimiyo: “¿Está perfectamente bien, Kimiyo?” I ask her. “Si. Está perfectamente bien,” she assures me.

We continue on with sentence #4: “Y, la cuatro, esta bien?” I ask them, speaking quickly and in a low voice, not even glancing at the sentence. They look at it and find something to be corrected, for several say, “No está bien.” I look at the sentence and see that the matters to be corrected are not so serious. “¿Y está muy mal?” I ask them with an expression which implies, “Come on... don’t exaggerate!” They carefully look at it again. “No esta muy mal,” some timid voices say. “iAhhh!... ¿Está un poco mal?” I ask them, making a gesture as I say un poco (a little). “Si... está un poco mal,” they tell me in a very reassuring manner... It is just like having a conversation with native speakers of Spanish.

Indeed, I find this stage offers a perfect opportunity to introduce my students to some ad hoc expressions. I try, however, to be careful not to overdo the number of such expressions. As we go along, besides keeping track of what I present them with, I bear in mind two things: a) I must always follow a logical sequence, and b) the expressions should —as much as possible— be considered useful and usable in future classes. Sometimes, in fact, I find this to be a very effective way to put them in touch with some grammatical points. In this case, for example, they have been introduced to está, third person, singular of the verb estar (one of the two Spanish equivalents of the verb to be), as well as a couple of adverbs… However, what matters is not the words themselves, but the fact that they have been given the opportunity to meet them by using them immediately through real situations, and that the situations have made the meaning crystal clear to them. It’s important as well, I think, to consider the fact that they were ready for such situations: they knew, for example, how to pronounce Spanish; they had begun to have a feeling for how the words sound in Spanish when they are put together; they had learned to make sense of what was put in front of them...

===================================

(The pages above are part of Discovering the Silent Way by John and Susana Pint, a displaced –if not quite lost – manuscript which we are interested in publishing. For more information, please contact us through www.saudicaves.com/silentway .)

John and Susy Pint