The Ghosts of San Marcos Train Station Photo: John Pint; Yaqui Girl: www.firstpeople.us; small images: John Kenneth Turner |

San Marcos Station:

Silent witness to the

enslavement and attempted genocide of Mexico’s Yaqui Indians

John Pint

The Ghosts of San Marcos Train Station Photo: John Pint; Yaqui Girl: www.firstpeople.us; small images: John Kenneth Turner |

While paging through an archeological guide to western Mexico, I came upon a

cryptic reference to the long-abandoned train station near the small town of San

Marcos, Jalisco, located 80 kilometers west of Guadalajara, Mexico's second

largest city. It said, “Yaquis were sold here (as slaves) for 25 centavos a

head… Around the station were located concentration camps where hundreds of

native people died of hunger and disease.”

I was surprised, to say the least, and, of course, curious to know more about

what went on in this train station, so I asked my Mexican friends if they ever

heard of a connection between a persecution of the Yaquis and San Marcos.

“Yes, said conservationist Rodrigo Orozco. “There’s a famous book on the Yaquis.

It’s actually a translation of a book in English called Barbarous Mexico

by John Kenneth Turner.”

"Barbarous Mexico" by Turner

Naturally, I turned to the Internet to learn more about the book, but I never

dreamed that in two minutes I would be able to download the entire text into my

computer. Barbarous Mexico, it seems was published in 1911 and is now in the

public domain. Yes, I found the complete book, free of charge at

Google Books, but two weeks later it was

no longer listed. Apparently, however, it is still available as a free Ebook

from Barnes & Noble.

Barbarous Mexico is not an attack upon the Mexican people, but an exposé

of the atrocities committed against many of them by President Porfirio Diaz

during 34 years of repeated "unopposed reelection." One of the worst schemes of

the Diaz government, says Turner, was the provocation of the Yaqui Indians to

rebellion in order to clear them out of Sonora so their land—rich for both mines

and agriculture—could be sold to Americans.

|

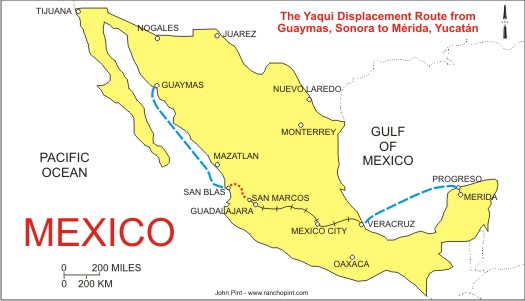

The Yaquis were put on boats at Guaymas and shipped to San Blas, where they

were forced to walk over 300 kilometers to San Marcos. Here were large

concentration camps where the Yaqui families were broken up. Individuals

were then sold inside the station and packed into train cars which took them

to Veracruz. Another boat ride brought them to Progreso in Yucatán, from

which they were taken to the plantation which would be their tomb. |

|

|

When he asked for concrete examples, the jailed Mexicans told him that great

numbers of people were being bought and sold like cattle and forced to work

on sisal plantations until they dropped dead—even though Mexico had

abolished slavery many years before.

|

|

Here he discovered that the Yaquis were indeed slaves in the worst sense of the word, beaten bloody every morning at role call, forced to work in the blazing sun from dawn to dusk on little food, locked up every night, and beaten again if they failed to cut and trim at least 2000 henequen leaves per day. The Yaqui women, separated from their families, were forced to “marry” Chinamen and every baby born on the plantation was worth up to $1000 cash to the owner. At least two-thirds of the Yaquis arriving in Yucatan were dead before the end of the first year of such treatment.

Turner was able to interview some of the slaves. One man with a baby on his arm,

said he was plowing in his field when the soldiers came. “They did not give me

time to unhitch my oxen,” he said.

“Where is the mother of your baby?” inquired Turner.

“Dead in San Marcos,” replied the young father. “That three weeks’ tramp over

the mountains killed her.”

|

Indeed, Turner’s informants agreed that “the crudest part of the trail was

between San Blas and San Marcos “where women with babies fell down on the

roadside, never to get up again.”

|

|

Those who grew rich from the atrocities of those days were, of course, Porfirio

Diaz, his relatives and cronies, but the book points out that more than half the

sisal was shipped to the USA and Turner accuses wealthy families such as the

Hearsts, the Rockefellers and the Guggenheims of having profited the most from

the expropriated lands of the Yaquis and Mayas as well as the “Flaming Hell” of

the henequen plantations.

|

The Yaqui people were famed for being hard-working and strong. Between 1904

and 1909, around 15,000 of them were rounded up, forced along the tortuous

route to Yucatán and enslaved. Despite their extraordinary strength, most of

them died within the first year on the plantations, raising questions of

whether they were the victims of genocide. Slave Mother and Child with Henequen Plant -- From Barbarous Mexico by John K. Turner. |

|

|

Hoping to find something in writing about this subject, we went off to the

town’s church where the local priest told us that any records that might

help us were not kept in San Marcos but would be found at Etzatlán.

|

|

|

Left: Juan Díaz and his daughter Livier help us search for information in San Marcos. Right: Susy Pint and Livier Díaz scour documents in the San Marcos library. |

We did, however, find one written reference suggesting that—in the early

1900’s—someone in San Marcos had objected to the government’s nefarious

operations in the area. It seems that when the Revolution broke out in 1911,

Porfirio Diaz immediately installed a military garrison at San Marcos and

federal soldiers searched day and night in the area for rebels, without

discovering that the biggest rebel of all, a certain Ramón Romero Paredes

lived right in San Marcos itself, where he was plotting an attack against

the garrison.

Ramón Romero's Nonchalant Escape

Unfortunately for the rebel, someone betrayed his presence to the

authorities and soon the town was surrounded by troops, making it utterly

impossible for anyone to slip away unnoticed. Romero, the story goes, was

unperturbed by all this and remained calm. He disguised himself as a peon,

with huaraches on his feet and a battered sombrero on his head. Smoking the

cheapest kind of cigarette (cigarrillo de hoja) he slowly wandered

over to the very officer in charge of his capture, to whom he offered a

smoke. With an icy voice, the officer snarled, “Get lost and leave me

alone.” Romero then walked right through the blockade and made his escape.

Hu-Dehart's Scholarly Overview of the Yaquis' Fate

A week after visiting the San Marcos library, I received a

surprise from archeologist Rodrigo Esparza: a 23-page paper published by Duke

University Press entitled

Development and Rural Rebellion: Pacification of the Yaquis in the Late

Porfiriato by Evelyn Hu-Dehart, a professor of history at Washington

University in St. Louis. This document was a dispassionate study of the Yaquis’

fate in contrast to Turner’s passionate book, which is often called the Uncle

Tom’s Cabin of slavery in early 20th century Mexico.

I discovered that Hu-Dehart confirmed the great majority of Turner’s claims,

with the notable exception of his assertion that the Yaquis were essentially

peaceful. “The Diaz government did not provoke the Yaqui rebellion, but

inherited it,” says Hu-Dehart, who points out that the Yaquis inevitably sided

with anyone fighting the authorities and refused to accept any deal giving them

less than the one thing they wanted: complete autonomy in their lush corner of

Sonora.

Interestingly, Hu-Dehart’s unemotional paper provides hard evidence for what

might seem Turner’s most controversial accusation: that the government of

Porfirio Diaz deliberately attempted the genocide of the Yaqui Indians. “The

government is… disposed to exterminate all of you if you continue to rebel,”

wrote General Lorenzo Torres to the chief of the Yaquis in 1908.

Hopefully, more information on the fate of the Yaquis at San Marcos will

come to light as time goes by. Meanwhile, I suggest that people who find

themselves in the area, perhaps visiting the

Great Stone Balls of Ahualulco, the huge

Palace of Ocomo at Oconahua or the

Circular Pyramids of Teuchitlán, might like to stop at the train

station, which is just off the main road, to reflect on the barbarous events

which took place there and perhaps to wander in the beautiful eucalyptus

grove. All other traces of the Yaquis’ passing have been obliterated, even

their cemetery, but their decomposing bodies probably helped give life to

those tall, proud trees and perhaps they are the best memorial of all to the

innocent souls who were murdered at San Marcos.

How to Get to the San Marcos Train

Station

You can reach San Marcos by taking highway 15 out of Guadalajara and

following the signs for Ameca. After passing the large sugar refinery at

Tala, turn right onto the road to Ahualulco and Etzatlán. Keep going west

another twelve kilometers past Etzatlán to reach San Marcos. You’ll see the

old train station on your left, 1.3 kilometers before reaching the town (GPS

location: 13 Q 584314 2297864). Driving time is about an hour from the Guadalajara Periférico.

See the VIDEO on YOUTUBE