Higuerita Cave: All the Way to the

Bottom!

Text and Photos ©2010 By John Pint unless otherwise noted

Don’t miss the action! See this story on Youtube!

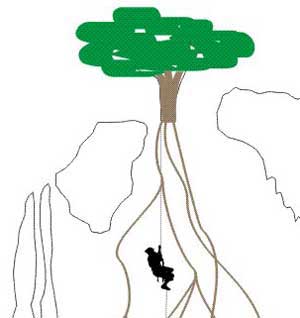

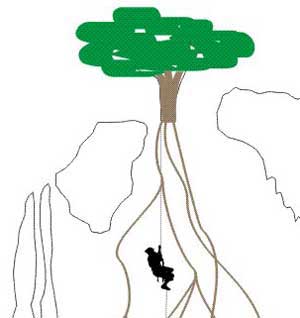

“Mario

has found a new pit at

Canutillo—who wants to go?” read the email I sent out to the cavers of Zotz,

Filostoc and CEO. A week later a dozen people showed up in Pinar de la Venta

where various arrangements of ropes were waiting for them, hanging from the

trees around my house. Each tree presented different ascending and descending

challenges, none of which slowed down these enthusiastic cavers for more than a

few minutes.

“Mario

has found a new pit at

Canutillo—who wants to go?” read the email I sent out to the cavers of Zotz,

Filostoc and CEO. A week later a dozen people showed up in Pinar de la Venta

where various arrangements of ropes were waiting for them, hanging from the

trees around my house. Each tree presented different ascending and descending

challenges, none of which slowed down these enthusiastic cavers for more than a

few minutes.

“Amigos, all of you are obviously ready for the Cave. Off we go next week.”

Canutillo is a small settlement located 50 kilometers east of Colima City. In

2008 we had explored and mapped a horizontal cave nearby (La

Cueva del Real) which turned out to have 185 meters of intertwining

passages, well decorated with stalactites, stalagmites and flowstone. We had

high hopes that La Cueva del la Higuerita (Little-Fig-Tree Cave) would have

equally fascinating galleries at the bottom of its imposing vertical entrance.

Although Mario Guerrero, finder of the pit, was unable to join us after all, due

to illness, eight other cavers showed up for the trip on the weekend of May

15-16. As soon as we got off the autopista, we noticed that something had

changed drastically along the road to Canutillo. Previously, we had hardly seen

even a single vehicle on this picturesque brecha which winds its way to

higher and higher elevations through majestic, pine-covered hills, all the way

up to an incredible place called

Puerto del Aire where

an icy wind can knock you off your feet in the middle of summer.

Now,

however, we found hundreds of heavily loaded trucks coming the opposite way we

were heading. This non-stop procession had ground the road’s surface into

extremely fine red powder which filled the air with choking dust and coated all

the trees and plants on both sides of the road, transforming the previously

beautiful Sierra del Alo (also known as Sierra Lalo) into the kind of

apocalyptic scene where you’d expect to see Mad Max himself charging out of the

dust cloud at any moment.

Now,

however, we found hundreds of heavily loaded trucks coming the opposite way we

were heading. This non-stop procession had ground the road’s surface into

extremely fine red powder which filled the air with choking dust and coated all

the trees and plants on both sides of the road, transforming the previously

beautiful Sierra del Alo (also known as Sierra Lalo) into the kind of

apocalyptic scene where you’d expect to see Mad Max himself charging out of the

dust cloud at any moment.

After two hours of breathing more dirt than air, we pulled into Rancho Del Real

where we were planning to camp. Here, Don Juan, the owner of the ranch told us

that all these trucks were carrying ore from three iron mines which had just

opened in the hills above Canutillo. “The Chinese are buying the ore,” he told

us with a broad smile, “and they’re paying a lot more than market value for it.”

We set up camp next to the previously peaceful river and noticed that every hour

a tanker would come by and noisily fill up with river water “for the mining

project.” Fortunately, all the noise stopped after sunset.

|

Those of us who arrived on Friday spent several of the afternoon hours

inside Del Real Cave. Leonel and “Saltamontes” went off looking for bats

while I somehow managed to talk “Mad Dog” Mitch and “Dracula” Rojas into

doing some experimental cave photography. The idea was to produce

good-looking side-lit pictures using nothing more than two point-n-shoot

cameras.

Vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) found inside the cave.

|

|

Zotz Cave-Photo Tip

First I set my Nikon Coolpix camera on “museum.” This setting is

designed for low-light situations in which flash cannot be used and the camera

is hand-held, like in museums, for example! I now aim my camera at the subject,

press the shutter button while saying “1, 2, 3” and my friend standing on one

side at about a 45° angle, pointing his camera at the same subject, takes a

flash picture on “2.”

Results? In most cases, the subject was in focus and nicely side lit with

pleasing shadows. The results were best when it was possible to immobilize the

camera (of course a tripod would be best) and the system works fine using

ten-second delay.

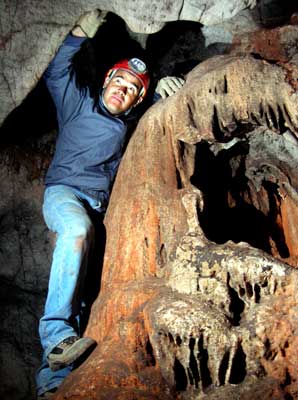

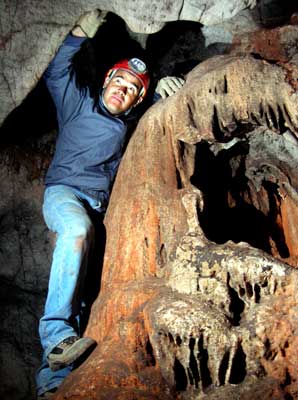

Left: The Zotz two-flash system

produces rich shadows (especially just below Mitch's hand).

Right:Typical Point-and-Shoot photo

using the camera’s own flash: flat and dull |

Saturday

morning the second contingent arrived: Coco, Matacanes and Molo. Speculating on

how long it will be before Chinese becomes Mexico’s second language, we cavers

loaded ourselves with ropes and vertical climbing gear and started up a steep

slope covered with slippery pine needles.

At the top, we came to a gaping maw in the limestone rock: the

awesome entrance to Higuerita Cave, only the “little fig tree” of bygone years

was now a Big Fig, conveniently located at the edge of the dark chasm, just

where we needed to place our rope for the rappel.

While the drop was being rigged, we suddenly heard the voice of Luis Rojas

wafting up from the bottom of the cave. He had downclimbed a narrow, vertical

tube and beat all of us to the punch!

On Rope in Little-Fig Cave

| Well, the dramatic-looking pitch turned out to be a mere 14 meters deep and very

quickly the other seven of us were also on the bottom. We found ourselves in a

room only 21 meters long and immediately set ourselves to investigating every

hole around the perimeter, hoping we might find the huge passage of our dreams,

just beyond.

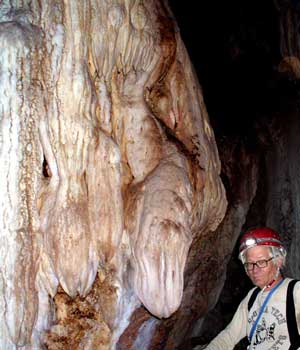

Mitch Ventura admiring the long fig-tree roots

contrasted against the flowstone wall.

|

|

| Some of these brought the total depth of the cave to 22 meters,

but, alas, none of these openings went very far and there was only one direction

we could go next: back up to the top.

Detail of cave

map. Click on it to see the complete profile and plan maps of Higuerita Cave.

|

|

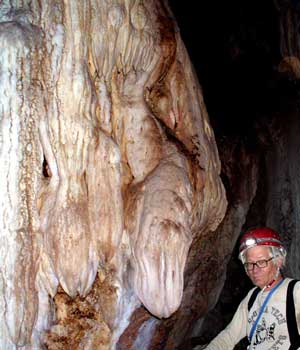

| ...However, I should mention that two of the cave’s walls were covered with beautiful flowstone and we spent

lots of time taking photos before connecting our ascenders to the rope and

heading back to the surface.

Photo by Rodrigo

"Molo" Terán. Oops, I forgot to smile and we also

forgot to try out our new 2-flash system at the bottom of the pit...this

nice flowstone would certainly have benefited!

|

|

Speleo Health Tips

Once on top, I opened my canteen and took a long, leisurely drink.

“You won’t get much benefit from your water if you drink it that way,” commented

Rojas.

Well, I never thought I would need lessons in how to take a drink of water, but

Rojas’ comments proved interesting. “When you’re hiking and you swallow water

right down, it can only hydrate your body via your stomach,” he said. “Instead,

if you take a sip and vigorously swish it around your mouth before swallowing,

the water will remove the coating that automatically forms on your palate,

thereby allowing it to instantly absorb the water and immediately hydrate the

tissues of your face. Try it on a long, hard, hot, hike and you’ll see the

difference.”

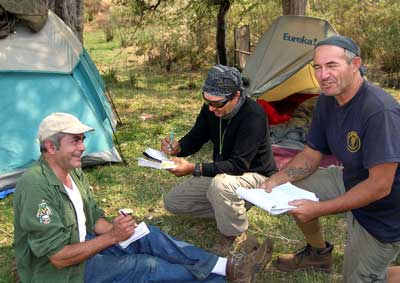

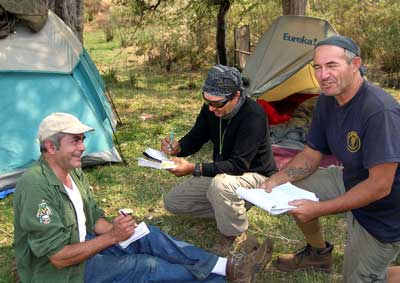

This exchange spurred a health-related discussion that went on while we derigged

the cave and which continued once we were back at our campsite.

This exchange spurred a health-related discussion that went on while we derigged

the cave and which continued once we were back at our campsite.

“I have gastritis,” said one caver.

“Drink Cuachalalate tea. You can find it in health food stores. Three cups a day

will fix you up.”

Soon, several of us had notebooks out and were jotting down one another’s

remedies. “Glucosamine-Chondroitin stopped my arthritis in its tracks ten years

ago.”

“Three glasses of lemonade at night cured my acid reflux totally.”

Eventually, the medical problem that kept Mario from this caving trip came up.

“He has a kidney stone,” we were told. This gave me a chance to relate my own,

painful experience with a kidney stone twelve years ago. “I rolled back and

forth across the living room floor all night long in agony,” I told the others,

believing I was about to die. A nurse later told me she had found passing a

kidney stone harder to bear than giving birth to her child. Lucky for me, my

next stone came along when I was in Mexico, and I got some free advice from Luis

Rojas. He told me to eat a little papaya every other day. I started doing this

then and there and have never had another kidney stone since.

Eventually, the medical problem that kept Mario from this caving trip came up.

“He has a kidney stone,” we were told. This gave me a chance to relate my own,

painful experience with a kidney stone twelve years ago. “I rolled back and

forth across the living room floor all night long in agony,” I told the others,

believing I was about to die. A nurse later told me she had found passing a

kidney stone harder to bear than giving birth to her child. Lucky for me, my

next stone came along when I was in Mexico, and I got some free advice from Luis

Rojas. He told me to eat a little papaya every other day. I started doing this

then and there and have never had another kidney stone since.

So, it seems to me that pearls of wisdom come not only from the mouths of babes,

but even from the mouths of muddy (but well-hydrated) cave explorers.

As for our return along the infamous Canutillo road, we were mercifully spared

the long string of roaring trucks because it was Sunday. However, we found

ourselves hopelessly stuck behind a bus full of miners all the way to Colima and

probably breathed in more choking dust on the way out than on the way in.

Leonel's Geyser

In honor of Mario Guerrero, who couldn’t make this trip, we had one of those

traditional major car breakdowns. Leonel’s radiator suddenly started boiling

over, making loud, rumbling noises and even produced a rather dramatic geyser.

By pure good luck (or the help of those guardian angels that watch over Mexicans

on mountain roads) this problem occurred right where there was a little spring

of cold, clear water gushing out of a pipe on the side of the dusty Canutillo

Road. Amazingly, with a little dishwashing detergent and a lot of water, the

oil-contaminated radiator was flushed out and: problema resuelto!

In honor of Mario Guerrero, who couldn’t make this trip, we had one of those

traditional major car breakdowns. Leonel’s radiator suddenly started boiling

over, making loud, rumbling noises and even produced a rather dramatic geyser.

By pure good luck (or the help of those guardian angels that watch over Mexicans

on mountain roads) this problem occurred right where there was a little spring

of cold, clear water gushing out of a pipe on the side of the dusty Canutillo

Road. Amazingly, with a little dishwashing detergent and a lot of water, the

oil-contaminated radiator was flushed out and: problema resuelto!

Mexicans, in case you didn’t know, are blessed with highly efficient guardian

angels who normally manage to turn the most disastrous mechanical failure into

something fixable with baling wire and chewing gum—and this was no exception.

Too bad there was no such angel around to restore the ravaged hills of Sierra

del Alo back to their pristine beauty!

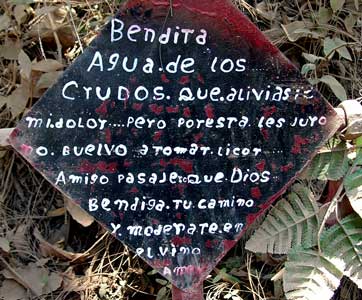

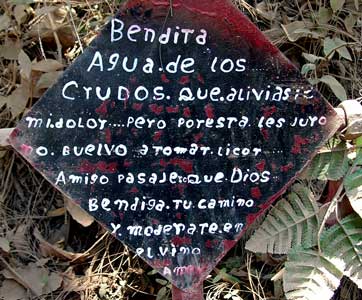

An

added benefit of our breakdown was the discovery of this curious message

next to the cold spring explaining that the water is great for

hangovers, but recommending a life of sobriety. Unfortunately, Luis

Rojas (right) didn't get the message! An

added benefit of our breakdown was the discovery of this curious message

next to the cold spring explaining that the water is great for

hangovers, but recommending a life of sobriety. Unfortunately, Luis

Rojas (right) didn't get the message! |

Goodbye, Canutillo! Until those three mines peter out, I’m afraid we’ll not be

back, not for all the iron in China!

Don’t miss the action!

See this story on Youtube!

Molo on rope

Leonel in Del Real Cave (PnS

camera with offset PnS flash)

“Mario

has found a new pit at

Canutillo—who wants to go?” read the email I sent out to the cavers of Zotz,

Filostoc and CEO. A week later a dozen people showed up in Pinar de la Venta

where various arrangements of ropes were waiting for them, hanging from the

trees around my house. Each tree presented different ascending and descending

challenges, none of which slowed down these enthusiastic cavers for more than a

few minutes.

“Mario

has found a new pit at

Canutillo—who wants to go?” read the email I sent out to the cavers of Zotz,

Filostoc and CEO. A week later a dozen people showed up in Pinar de la Venta

where various arrangements of ropes were waiting for them, hanging from the

trees around my house. Each tree presented different ascending and descending

challenges, none of which slowed down these enthusiastic cavers for more than a

few minutes. Now,

however, we found hundreds of heavily loaded trucks coming the opposite way we

were heading. This non-stop procession had ground the road’s surface into

extremely fine red powder which filled the air with choking dust and coated all

the trees and plants on both sides of the road, transforming the previously

beautiful Sierra del Alo (also known as Sierra Lalo) into the kind of

apocalyptic scene where you’d expect to see Mad Max himself charging out of the

dust cloud at any moment.

Now,

however, we found hundreds of heavily loaded trucks coming the opposite way we

were heading. This non-stop procession had ground the road’s surface into

extremely fine red powder which filled the air with choking dust and coated all

the trees and plants on both sides of the road, transforming the previously

beautiful Sierra del Alo (also known as Sierra Lalo) into the kind of

apocalyptic scene where you’d expect to see Mad Max himself charging out of the

dust cloud at any moment.

This exchange spurred a health-related discussion that went on while we derigged

the cave and which continued once we were back at our campsite.

This exchange spurred a health-related discussion that went on while we derigged

the cave and which continued once we were back at our campsite. Eventually, the medical problem that kept Mario from this caving trip came up.

“He has a kidney stone,” we were told. This gave me a chance to relate my own,

painful experience with a kidney stone twelve years ago. “I rolled back and

forth across the living room floor all night long in agony,” I told the others,

believing I was about to die. A nurse later told me she had found passing a

kidney stone harder to bear than giving birth to her child. Lucky for me, my

next stone came along when I was in Mexico, and I got some free advice from Luis

Rojas. He told me to eat a little papaya every other day. I started doing this

then and there and have never had another kidney stone since.

Eventually, the medical problem that kept Mario from this caving trip came up.

“He has a kidney stone,” we were told. This gave me a chance to relate my own,

painful experience with a kidney stone twelve years ago. “I rolled back and

forth across the living room floor all night long in agony,” I told the others,

believing I was about to die. A nurse later told me she had found passing a

kidney stone harder to bear than giving birth to her child. Lucky for me, my

next stone came along when I was in Mexico, and I got some free advice from Luis

Rojas. He told me to eat a little papaya every other day. I started doing this

then and there and have never had another kidney stone since. In honor of Mario Guerrero, who couldn’t make this trip, we had one of those

traditional major car breakdowns. Leonel’s radiator suddenly started boiling

over, making loud, rumbling noises and even produced a rather dramatic geyser.

By pure good luck (or the help of those guardian angels that watch over Mexicans

on mountain roads) this problem occurred right where there was a little spring

of cold, clear water gushing out of a pipe on the side of the dusty Canutillo

Road. Amazingly, with a little dishwashing detergent and a lot of water, the

oil-contaminated radiator was flushed out and: problema resuelto!

In honor of Mario Guerrero, who couldn’t make this trip, we had one of those

traditional major car breakdowns. Leonel’s radiator suddenly started boiling

over, making loud, rumbling noises and even produced a rather dramatic geyser.

By pure good luck (or the help of those guardian angels that watch over Mexicans

on mountain roads) this problem occurred right where there was a little spring

of cold, clear water gushing out of a pipe on the side of the dusty Canutillo

Road. Amazingly, with a little dishwashing detergent and a lot of water, the

oil-contaminated radiator was flushed out and: problema resuelto!

An

added benefit of our breakdown was the discovery of this curious message

next to the cold spring explaining that the water is great for

hangovers, but recommending a life of sobriety. Unfortunately, Luis

Rojas (right) didn't get the message!

An

added benefit of our breakdown was the discovery of this curious message

next to the cold spring explaining that the water is great for

hangovers, but recommending a life of sobriety. Unfortunately, Luis

Rojas (right) didn't get the message!