“Thirty-six, thirty-seven, thirty-eight…” We were standing waist-deep in the

fish pool at a restaurant on the shore of Lake La Vega. I (John) was holding a net and

Professor José Luis Zavala, a biologist at Guadalajara’s Autonomous University,

was doing the impossible: counting fish which had been extinct for years.

“Thirty-six, thirty-seven, thirty-eight…” We were standing waist-deep in the

fish pool at a restaurant on the shore of Lake La Vega. I (John) was holding a net and

Professor José Luis Zavala, a biologist at Guadalajara’s Autonomous University,

was doing the impossible: counting fish which had been extinct for years.

|

“These are Ameca splendens,” Zavala had told me before we jumped into the pool.

“They are members of the Goodeid family, some of the best loved aquarium fishes

in the world. They were pronounced extinct several years ago, but somehow they

are still thriving in this little pool.”

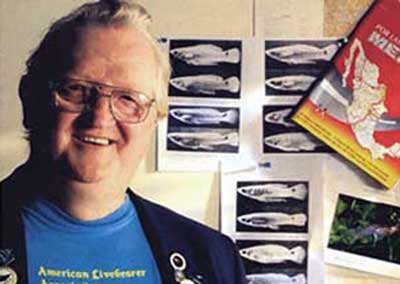

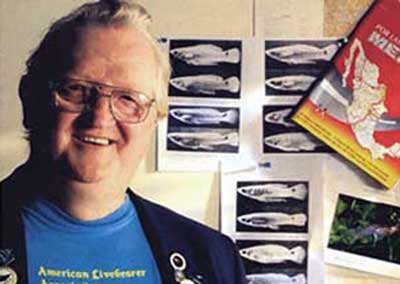

John Pint (left)

and José Luis Zavala counting "extinct" fish.

|

|

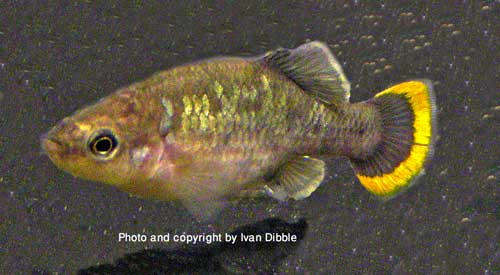

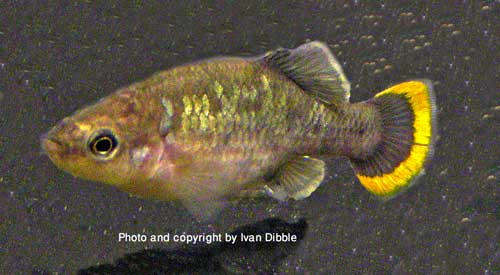

The Goodeids or Splitfins are a family of some 40 species, all endemic to

Mexico. They reproduce by internal fertilization and bear their young live. They

happen to love algae, and will keep an aquarium free of it. On top of that, they

are remarkably beautiful. Ameca splendens and other Goodeids were discovered in

the Rio Teuchitlán long ago and were soon being bred in captivity by fish

fanciers around the world.

One of these was Ivan Dibble, an Englishman who has

been specializing in livebearers since the 1960’s. At a convention in 1995,

Dibble met Arcadio Valdes Gonzales, who brought him bad news from Mexico. Ameca

splendens and several other Goodeids endemic to the area around Ameca had

vanished and were now considered extinct.

Ivan Dibble

in England. |

|

Verifying this was not difficult, as

the Teuchitlán river bubbles out of the ground at a spring near the famed

Guachimontones Pyramids and trickles into La Presa de la Vega only a few

kilometers away. The fish had not been spotted anywhere along this trajectory

and they couldn’t possibly survive in La Vega Lake because it has been polluted

for decades by the government-owned Tala sugar refinery, even though dumping

contaminants into the lake is against Mexican law. To make matters worse, the

refinery people mix chemicals from sugar processing with ground-up cane stalks.

“They are putting nutrients into the dam which accelerates the growth of water

hyacinths which in turn are suffocating the lake,” says naturalist Jesus Moreno.

Black muck from the

sugar refinery (Left) kills the fish while accelerating the growth of

water hyacinths (Right). |

Although these delicate little fish cannot survive in La Vega Lake, some of them

are still alive in pools at the restaurants along the lakeshore, because all of

these are spring-fed. Unfortunately, the pools are not there for appreciating

the fish, but for catching them, a favorite sport for countless little children

on a typical weekend.

In 1997, Dibble attended a symposium in Cuernavaca and discovered that the

problem of vanishing native fish species was wide-spread all over Mexico. “I

have almost always risen to a challenge,” says Dibble and he decided to take on

the nearly impossible task of saving Mexico’s fish. After the symposium in

Cuernavaca, Dibble was taken to an Aquatic Laboratory Facility in Morelia, run

by the University of Michoacán. They offered to participate in a conservation

project to preserve native Mexican fresh-water species.

|

Dibble flew off to

England, but returned to Mexico a few months later with two species of fish

thought to be extinct in the wild, Skiffia francesae and Zoogoneticus tequila,

both of which are now reproducing happily in Michoacán.

Zoogoneticus tequila. |

|

As with most conservation projects, finance is a key element. The lab did not

have a budget for a big project, so Dibble decided to contact livebearer hobby

groups, asking for donations. The result was the Hobbyist Aqua Lab Conservation

Project (Mexico) or Fish Ark Mexico, for short. Hobbyists from all over the

world have rallied to the project and the funds are being used to purchase new

equipment and to continually expand the project. “Today all the members of the

Goodeid Family are being maintained and bred in the Ark and the people in

Morelia have also made a start with other livebearers.”

| THE AMECA

PROJECT Ivan Dibble's most recent

(and, indeed last) project involves the creation of a Goodeidae breeding pool along the Teuchitlan

River. The help of local authorities and ichthyologists will be needed, as

well as support from the general public.

Susy Pint examines a possible site for the

breeding pool on the banks of the Teuchitlan River, about 870 meters north

of the highway to Teuchitlan. Ameca splendens is alive and well in this part

of the river, but not farther downstream, which is polluted.

|

|

The mission of Ivan Dibble and friends is outlined at his

Fish Ark Mexico page (http://home.clara.net/brachydibble/). Check it out and perhaps you too will

decide to help the British save Mexico’s fish.

Bridal veil used to catch

Ameca splendens for the photo above.

John photographing the

little fish.

Matias of Switzerland

kissing fish (note the size: this is an adult).

Susy Pint alongside the lovely Teuchitlán

River.

“Thirty-six, thirty-seven, thirty-eight…” We were standing waist-deep in the

fish pool at a restaurant on the shore of Lake La Vega. I (John) was holding a net and

Professor José Luis Zavala, a biologist at Guadalajara’s Autonomous University,

was doing the impossible: counting fish which had been extinct for years.

“Thirty-six, thirty-seven, thirty-eight…” We were standing waist-deep in the

fish pool at a restaurant on the shore of Lake La Vega. I (John) was holding a net and

Professor José Luis Zavala, a biologist at Guadalajara’s Autonomous University,

was doing the impossible: counting fish which had been extinct for years.